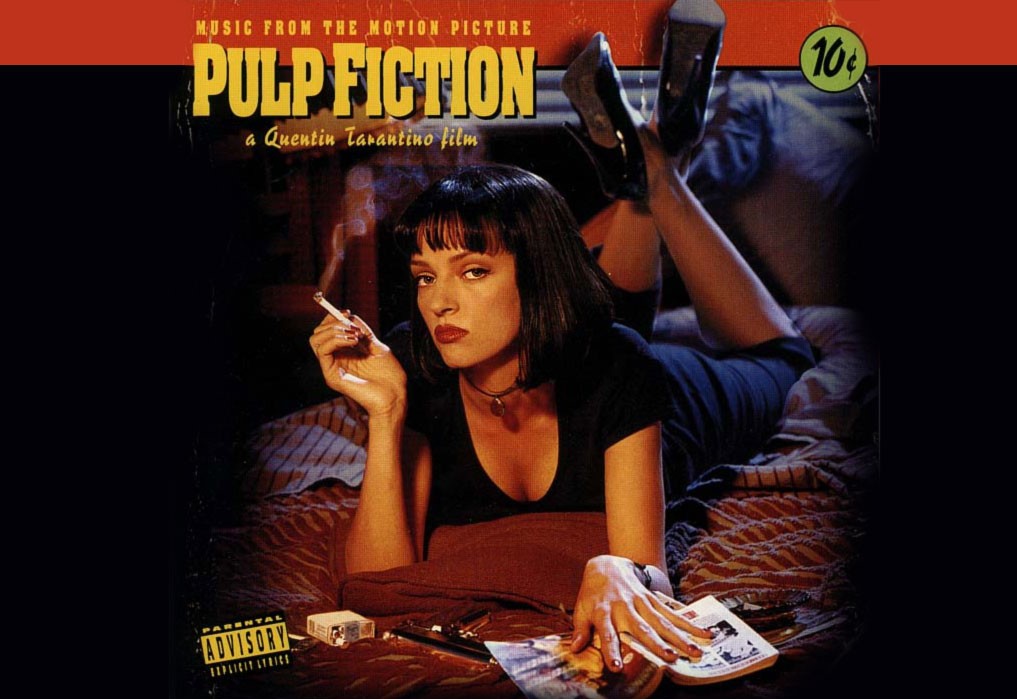

In 1994, Firooz Zahedi, a photographer, took several photographs of Uma Thurman in character in her now-famous role as Mia Wallace in the Quentin Tarantino film Pulp Fiction. Miramax, the studio that produced Pulp Fiction, used one of Zahedi’s photographs, with some changes (including changing the position of the gun on the bed in front of Ms. Thurman) on its poster for the film.

In 1994, Firooz Zahedi, a photographer, took several photographs of Uma Thurman in character in her now-famous role as Mia Wallace in the Quentin Tarantino film Pulp Fiction. Miramax, the studio that produced Pulp Fiction, used one of Zahedi’s photographs, with some changes (including changing the position of the gun on the bed in front of Ms. Thurman) on its poster for the film.

The poster was used to promote the film at the Cannes Film Festival in 1994, as well as for the film’s theatrical release later that year. At the time of the photo shoot, Miramax paid Zahedi $10,000, although exactly what Miramax Film was paying for is the subject of these motions.

Neither party has produced a signed agreement identifying what rights either party retained in the photograph. Miramax obtained a copyright registration for the poster as a “key art transparency” from the Register of Copyrights in 2003. On Miramax’s copyright registration, Miramax checked the box to register a “2 Dimensional artwork,” not a photograph, and does not identify Zahedi as a contributor at all.

Zahedi obtained a copyright registration for his photograph in 2019. Zahedi’s copyright registration states the title of the work is “Poster for Pulp Fiction” and identifies the work as a photograph.

The Creation of the Photograph

Miramax’s Story

In Miramax’s version, Miramax developed the concept for the image and hired Zahedi to execute its vision, buying out all the rights. Tod Tarhan, a former Miramax art director who worked on the campaign for Pulp Fiction in 1994, described the process by which he and the rest of the Miramax team developed the concept for the Zahedi shoot.

He and colleagues developed the idea of depicting Uma Thurman as a “femme fatale,” including deciding on Ms. Thurman’s pose. Tarhan says he developed sketches for the poster in late 1993 or early 1994. The sketches are very similar to the image used in the Pulp Fiction poster: they depict Ms. Thurman lying on a bed in the pose used in the photograph, holding a book, with a gun lying on the bed in front of her.

Miramax paid the expenses for the photoshoot. Several Miramax witnesses testified that Miramax would not have hired Zahedi without a work-for-hire agreement. A very large number of Miramax files, however, are difficult to search. The documents have been in boxes since 2001, and were shipped across the country after Miramax’s New York offices closed in 2010 without a detailed inventory being performed. The files’ organization has been further disrupted by subsequent sales of the company. Miramax has not found a work for hire agreement.

Zahedi’s Story

In Zahedi’s version of what transpired, Zahedi took a low fee to work on an interesting shoot for a hotly-anticipated indie film project, and created an iconic and beloved image. In Zahedi’s version, his agent, Janet Botaish, was approached by Miramax for a photo shoot relating to Pulp Fiction in 1994. Miramax had a limited budget and offered Zahedi $10,000, below Zahedi’s standard fee, but Zahedi accepted because he was interested in the project.

The parties did not execute a work-for-hire agreement or other “buyout” agreement because Miramax “didn’t do contracts.” Zahedi orally licensed to Miramax the right to use the photograph on a physical poster to promote the movie, but did not otherwise grant Miramax a license to use the photograph. When the poster won a “Key Art” award from the Hollywood Reporter in 1994, Zahedi was credited as the photographer.

Uses Since 1994

Miramax has used the poster widely since Pulp Fiction’s release in 1994. Beginning in 1995, the poster appeared on the sleeve of VHS tapes that were available at Blockbuster and other stores. Beginning in 1996, the poster was used on the sleeve of LaserDiscs. Miramax says it always attached a copyright notice identifying Miramax as the copyright holder.

A 1994 script for the film published by Miramax Books, however, identifies the cover photograph (Zahedi’s photograph) as copyright Firooz Zahedi. The image has also appeared on T-shirts, socks, and other merchandise. In 2015, Zahedi received a Mia Wallace action figure as a gift. The packaging for the action figure prominently featured the poster. The action figure also had a Miramax copyright mark.

In 2019, Zahedi received another gift featuring his photograph, this time a pair of socks. It was this gift that caused Zahedi to file his registration of copyright, to contact Miramax, and eventually to file this lawsuit. Zahedi filed his complaint on May 19, 2020 and asserted claims for copyright infringement and vicarious or contributory copyright infringement against Miramax and 26 other defendants.

Miramax moved for summary judgment as to Zahedi’s entire complaint. Miramax argued that Zahedi’s claims are barred by the statute of limitations or, in the alternative, by the equitable doctrines of estoppel and laches, and that in any event Miramax, not Zahedi, owns the photograph as a work for hire. Zahedi moved for summary judgment as to the issues of his ownership of the photograph and on Miramax’s statute of limitations defense.

Statute of Limitations

A civil action for copyright infringement must be brought “within three years after the claim accrued.” In the Ninth Circuit, this means that in general, a plaintiff cannot recover for damages that occurred more than three years before suit was filed. There is an exception if a plaintiff lacked knowledge of the infringement prior to the three-year period preceding filing suit, and if that lack of knowledge was reasonable.

Ninth Circuit case law distinguishes, however, between “infringement” claims and “ownership” claims. Unlike infringement claims, “ownership claims accrue only once, at the time ‘when plain and express repudiation of co-ownership is communicated to the claimant, and are barred three years from the time of repudiation,’ because ‘an infringement occurs every time the copyrighted work is published, but creation does not.’”

The gravamen of this case is ownership. Where the gravamen of a claim is ownership, the statute of limitations will bar a claim if (1) the parties are in a close relationship and (2) there has been an “express repudiation” of the plaintiff’s ownership claim. Zahedi argues first that he is not in a “close relationship” with Miramax, and second that Miramax did not clearly and expressly repudiate his ownership.

Close Relationship

Zahedi argues he does not have a “close relationship” with Miramax, LLC. He notes that in other cases in which courts have found a “close relationship,” the parties had entered into contracts or express agreements regarding the work in question. There is no dispute that even if Zahedi owns the copyright in his photograph, he took the photograph at Miramax Film Corp.’s request and granted Miramax Film Corp. at least a limited license to use it for certain purposes.

Zahedi had a prior business relationship and at least a verbal agreement with Miramax regarding his photograph. Zahedi also argues that he was not in contractual privity with Miramax, LLC; rather, his agreement was with Miramax, LLC’s predecessor, Miramax Film Corp. This distinction is not determinative, however, with regard to whether Zahedi and Miramax had a close relationship.

Zahedi contracted with Miramax’s predecessor-in-interest. Zahedi knew Miramax, LLC was exploiting the photograph. Based on the definition established by binding Ninth Circuit authority, Zahedi and Miramax were in a close relationship.

Repudiation

Zahedi raises three arguments. First, Zahedi argues that Miramax’s copyright registration for the poster does not constitute an express repudiation of Zahedi’s ownership because it does not assert ownership of a photograph, but rather of a “2 Dimensional artwork.”

Second, Zahedi asserts that Miramax did not expressly repudiate Zahedi’s ownership by using its own copyright mark on items featuring the poster because Miramax credited Zahedi as the copyright holder of the photograph on the cover of the 1994 publication of the script.

Third, Zahedi contends that Miramax’s failure to pay him royalties for its use of the photograph does not constitute an express repudiation of his ownership.

Zahedi argues that Miramax’s copyright registration did not cover his photograph, and that the registration therefore did not serve as an express repudiation of his ownership of the photograph. His photograph and the poster are different: the photograph used on the poster is slightly altered from the original, and the poster also includes lettering and an “aging” effect to make it look like the tattered cover of a paperback.

Miramax did not check the “photograph” box on the copyright registration. Zahedi is correct that Miramax’s copyright registration does not provide constructive notice of Miramax’s claim of exclusive copyright ownership, because Miramax’s copyright registration could plausibly be understood to cover only the poster, and not the underlying photograph.

The Court need not decide whether Zahedi had constructive notice of Miramax’s repudiation, because he had actual notice. Where, as here, Zahedi actually knew that Miramax was exploiting a photograph of which he claimed ownership without giving him credit or royalties, his failure to bring suit to assert his ownership rights is fatal to his case.

Zahedi’s receipt in 2015 of an action figure prominently featuring the iconic photo, bearing Miramax’s copyright notice, and failing to credit Zahedi is uncontroverted evidence of his actual knowledge of Miramax’s plain and express repudiation of his ownership. It is clear that Zahedi understood in 2015 that Miramax claimed more rights in the photograph than Zahedi believed it had. Zahedi’s claim is therefore barred by the statute of limitations.