January 22, 2018, Adrian Falkner filed civil action, seeking relief for (1) copyright infringement and (2) falsification, removal, and alteration of copyright management information in violation of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. Defendant moved for summary judgment.

Factual Background

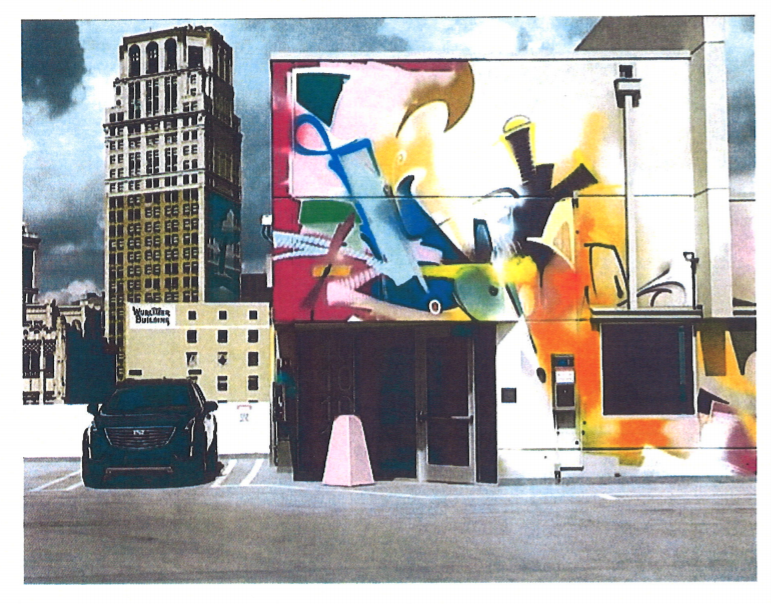

Adrian Falkner (Plaintiff) is an artist, producing works under the pseudonym “Smash 137.” In 2014, Plaintiff was invited by a Detroit art gallery to create an outdoor mural as part of a marketing project of murals to be displayed throughout a parking garage located at 1234 Library Street in Detroit, Michigan.

Plaintiff created such a mural on two perpendicular walls located in that parking garage. In so doing, Plaintiff placed his pseudonym, “SMASH 137,” on the left side of one of the walls that displayed his mural. Plaintiff was allowed to choose where in the garage to paint his mural, and was afforded complete creative freedom with respect to the mural.

Plaintiff was given no aesthetic to match and was not told of any function that the mural should play. Ultimately, Plaintiff chose to create the mural using themes and motifs that were similar to those used on the paintings that had been exhibited at a solo show long before he had heard of the mural project. In addition, the architecture of the parking garage and accompanying building were already complete before Plaintiff started painting.

In August 2016, Alex Bernstein, a professional automotive photographer, traveled to Detroit. Knowing that automotive companies generally maintain press fleets of vehicles for publicity purposes, Bernstein borrowed a car from Cadillac. During his trip, Bernstein took several photographs. One of them captured a portion of Plaintiff’s mural.

The photograph showed only one of the two walls constituting the mural, and the wall that was not included was the wall on which Plaintiff had placed his pseudonym. Bernstein claims that he did not see Plaintiff’s name or pseudonym on the mural.

Bernstein declares that he chose to frame his photograph in this particular manner because he liked the composition; it permitted him to include a portion of the Detroit skyline.

The mural wall that was included in the photograph does itself include a plaque that contains some copyright management information about Plaintiff, although it cannot be read in the photograph because of the distance from which the photograph was taken.

Bernstein sent the photographs he had taken in Detroit, including the photograph depicting Plaintiff’s mural, to Defendant. Defendant’s advertising agency posted Bernstein’s photograph of the mural on Defendant’s social media.

Donny Nordlicht, the General Motors employee who received the photographs, claims that neither he nor any other General Motors employee was aware that the photograph omitted a perpendicular wall displaying the mural or that the omitted wall contained Plaintiff’s pseudonym at the time the photograph was posted.

PGS Works, Architectural Works, and the Section 120(a) Exception to the Protection of Architectural Works

Despite the general protection of architectural works under 17 U.S.C. § 101, such protection is limited in specific contexts by 17 U.S.C. § 120(a). Under Section 120(a), “the copyright in an architectural work that has been constructed does not include the right to prevent the making, distributing, or public display of pictures, paintings, photographs, or other pictorial representations of the work, if the building in which the work is embodied is located in or ordinarily visible from a public place.”

Thus, one may freely take a photograph of an architectural work, including a “building,” without infringing a copyright in the work. This case presents a more complex issue: whether Section 120(a) applies to (and thus limits the copyright protection of) a PGS work that is physically connected to an architectural work.

Application of the Section 120(a) Exception

Existence of an “Architectural Work”

In order for the Section 102(a)(8) protection of architectural works to be implicated, there must be an architectural work. Defendant did not argue that the mural itself is an architectural work; thus, the only issue was whether the parking garage is an architectural work.

Based on the definition of the term “building,” it seems plainly clear that parking garages, including the one at issue, are “buildings” and thus architectural works for the purpose of Section 102(a)(8). Although people do not live at the parking garage at 1234 Library Street, it is fit for human occupancy and, even more clearly, it is used by human beings.

As noted by Defendant in its reply brief, the “owner of the parking structure would not have commissioned artists to paint murals on the inward-facing or interior walls of the structure if the structure were not to be ‘occupied’ or ‘used’ by human beings.”

Relationship Between the Mural and the Parking Garage

There is no indication that the mural was designed to appear as part of the building or to serve a functional purpose that was related to the building. Instead, there is undisputed evidence that Plaintiff was afforded complete creative freedom with respect to the mural, and that the design of the mural was inspired by Plaintiff’s prior work.

Plaintiff was not instructed that the mural should play a functional role with respect to the parking garage or that the design of the mural should match design elements of the garage. Indeed, the architecture of the parking garage and accompanying building were already complete before Plaintiff started painting.

Because the facts in the record tend to establish the lack of a relevant connection between the mural and the parking garage, the Court cannot hold as a matter of law that the mural is part of an architectural work under Section 102(a)(8).

Thus, it cannot reach the issue of whether Section 120(a) applies to the mural to permit photographs of the mural. Thus, Defendant’s motion for partial summary judgment on the copyright infringement claim has been DENIED.

The DMCA Claim

Plaintiff argues that Defendant “intentionally removed… copyright management information in the image used in Defendant’s advertisement, in that Defendant’s photograph of the Mural is taken from an angle that renders Plaintiff’s signature not visible.”

But a close reading of Plaintiff’s claim reveals that Plaintiff fails to explain how framing a photograph in a manner that excludes copyright management information constitutes “removal” or “alteration” of such information as required by the statute.

Because a Section 1202(b) claim cannot be won without establishing the removal or alteration of copyright management information, Defendant’s motion for partial summary judgment on the Section 1202(b) claim has been GRANTED.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.