This is a copyright infringement action brought by the photographer Jacobus Rentmeester against Nike. The case involves a famous photograph Rentmeester took in 1984 of Michael Jordan, who at the time was a student at the University of North Carolina. The photo originally appeared in Life magazine as part of a photo essay featuring American athletes who would soon be competing in the 1984 Summer Olympic Games.

Rentmeester’s photograph of Jordan is original. It depicts Jordan leaping toward a basketball hoop with a basketball raised above his head in his left hand, as though he is attempting to dunk the ball. The setting for the photo is not a basketball court, as one would expect in a shot of this sort. Instead, Rentmeester chose to take the photo on an isolated grassy knoll on the University of North Carolina campus. He brought in a basketball hoop and backboard mounted on a tall pole, which he planted in the ground to position the hoop exactly where he wanted. Whether due to the height of the pole or its placement within the image, the basketball hoop appears to tower above Jordan, beyond his reach.

Rentmeester instructed Jordan on the precise pose he wanted Jordan to assume. It was an unusual pose for a basketball player to adopt, one inspired by ballet’s grand jeté, in which a dancer leaps with legs extended, one foot forward and the other back. Rentmeester positioned the camera below Jordan and snapped the photo at the peak of his jump so that the viewer looks up at Jordan’s soaring figure silhouetted against a cloudless blue sky. Rentmeester used powerful strobe lights and a fast shutter speed to capture a sharp image of Jordan contrasted against the sky, even though the sun is shining directly into the camera lens from the lower righthand corner of the shot.

Not long after Rentmeester’s photograph appeared in Life magazine, Nike contacted him and asked to borrow color transparencies of the photo. Rentmeester provided Nike with two color transparencies for $150 under a limited license authorizing Nike to use the transparencies “for slide presentation only.” It is unclear from the complaint what kind of slide presentation Nike may have been preparing, but the company was then beginning its lucrative partnership with Jordan by promoting the Air Jordan brand of athletic shoes.

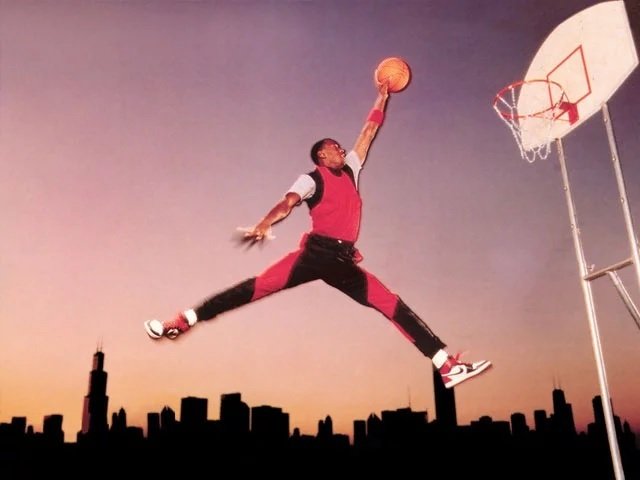

In late 1984 or early 1985, Nike hired a photographer to produce its own photograph of Jordan, one obviously inspired by Rentmeester’s. In the Nike photo, Jordan is again shown leaping toward a basketball hoop with a basketball held in his left hand above his head, as though he is about to dunk the ball. The photo was taken outdoors and from a similar angle as in Rentmeester’s photo, so that the viewer looks up at Jordan’s figure silhouetted against the sky. In the Nike photo, though, it is the city of Chicago’s skyline that appears in the background, a nod to the fact that by then Jordan was playing professionally for the Chicago Bulls. Jordan wears apparel reflecting the colors of his new team, and he is of course wearing a pair of Nike shoes. Nike used this photo on posters and billboards as part of its marketing campaign for the new Air Jordan brand.

When Rentmeester saw the Nike photo, he threatened to sue Nike for breach of the limited license governing use of his color transparencies. To head off litigation, Nike entered into a new agreement with Rentmeester in March 1985, under which the company agreed to pay $15,000 for the right to continue using the Nike photo on posters and billboards in North America for a period of two years. Rentmeester alleged that Nike continued to use the photo well beyond that period. In 1987, Nike created its iconic “Jumpman” logo, a solid black silhouette that tracks the outline of Jordan’s figure as it appears in the Nike photo. Over the past three decades, Nike has used the Jumpman logo in connection with the sale and marketing of billions of dollars of merchandise. It has become one of Nike’s most recognizable trademarks.

Rentmeester filed his action in January 2015. He alleged that both the Nike photo and the Jumpman logo infringe the copyright in his 1984 photo of Jordan. His complaint asserted claims for direct, vicarious, and contributory infringement, as well as a claim for violation of the DMCA. Rentmeester required damages only for acts of infringement occurring within the Copyright Act’s three-year limitations period (January 2012 to the present). The district court dismissed Rentmeester’s claims with prejudice after concluding that neither the Nike photo nor the Jumpman logo infringe Rentmeester’s copyright as a matter of law. The appeal court reviewed that legal determination de novo.

In this case, Rentmeester has plausibly alleged the first element of his infringement claim – that he owns a valid copyright. The complaint asserted that he has been the sole owner of the copyright in his photo since its creation in 1984. And the photo obviously qualifies as an “original work of authorship,” given the creative choices Rentmeester made in composing it. Nike’s access to Rentmeester’s photo, combined with the obvious conceptual similarities between the two photos, is sufficient to create a presumption that the Nike photo was the product of copying rather than independent creation. The remaining question is whether Rentmeester has plausibly alleged that Nike copied enough of the protected expression from Rentmeester’s photo to establish unlawful appropriation.

Photos can be broken down into objective elements that reflect the various creative choices the photographer made in composing the image – choices related to subject matter, pose, lighting, camera angle, depth of field, and the like. But none of those elements is subject to copyright protection when viewed in isolation. For example, a photographer who produces a photo using a highly original lighting technique or a novel camera angle cannot prevent other photographers from using those same techniques to produce new images of their own, provided the new images are not substantially similar to the earlier, copyrighted photo.

With respect to a photograph’s subject matter, no photographer can claim a monopoly on the right to photograph a particular subject just because he was the first to capture it on film. A subsequent photographer is free to take her own photo of the same subject, again so long as the resulting image is not substantially similar to the earlier photograph. That remains true even if, as here, a photographer creates wholly original subject matter by having someone pose in an unusual or distinctive way.

Without question, one of the highly original elements of Rentmeester’s photo is the fanciful (non-natural) pose he asked Jordan to assume. That pose was a product of Rentmeester’s own “intellectual invention”. Without gainsaying the originality of the pose Rentmeester created, he cannot copyright the pose itself and thereby prevent others from photographing a person in the same pose. He is entitled to protection only for the way the pose is expressed in his photograph, a product of not just the pose but also the camera angle, timing, and shutter speed Rentmeester chose.

If a subsequent photographer persuaded Michael Jordan to assume the exact same pose but took her photo, say, from a bird’s eye view directly above him, the resulting image would bear little resemblance to Rentmeester’s photo and thus could not be deemed infringing. What is protected by copyright is the photographer’s selection and arrangement of the photo’s otherwise unprotected elements. If sufficiently original, the combination of subject matter, pose, camera angle, etc., receives protection, not any of the individual elements standing alone. In that respect (although not in others), photographs can be likened to factual compilations. An author of a factual compilation cannot claim copyright protection for the underlying factual material – facts are always free for all to use.

If sufficiently original, though, an author’s selection and arrangement of the material are entitled to protection. The individual elements that comprise a photograph can be viewed in the same way, as the equivalent of unprotectable “facts” that anyone may use to create new works. A second photographer is free to borrow any of the individual elements featured in a copyrighted photograph, “so long as the competing work does not feature the same selection and arrangement” of those elements. In other words, a photographer’s copyright is limited to “the particular selection and arrangement” of the elements as expressed in the copyrighted image.

This is not to say, as Nike urged the court to hold, that all photographs are entitled to only “thin” copyright protection, as is true of factual compilations. A copyrighted work is entitled to thin protection when the range of creative choices that can be made in producing the work is narrow. Some photographs are entitled to only thin protection because the range of creative choices available in selecting and arranging the photo’s elements is quite limited. Rentmeester’s photo is undoubtedly entitled to broad rather than thin protection. The court concluded that the works at issue are as a matter of law not substantially similar. Just as Rentmeester made a series of creative choices in the selection and arrangement of the elements in his photograph, so too Nike’s photographer made his own distinct choices in that regard. Those choices produced an image that differs from Rentmeester’s photo in more than just minor details.

The two photos are undeniably similar in the subject matter they depict: both capture Michael Jordan in a leaping pose inspired by ballet’s grand jeté. But Rentmeester’s copyright does not confer a monopoly on that general “idea” or “concept”; he cannot prohibit other photographers from taking their own photos of Jordan in a leaping, grand jetéinspired pose. Because the pose Rentmeester conceived is highly original, though, he is entitled to prevent others from copying the details of that pose as expressed in the photo he took. Had Nike’s photographer replicated those details in the Nike photo, a jury might well have been able to find unlawful appropriation even though other elements of the Nike photo, such as background and lighting, differ from the corresponding elements in Rentmeester’s photo. But Nike’s photographer borrowed only the general idea or concept embodied in the photo.

The two photos again share undeniable similarities at the conceptual level: both are taken outdoors without the usual trappings of a basketball court, other than the presence of a lone hoop and backboard. But when comparing the details of how that concept is expressed in the two photos, stark differences are readily apparent. The other major conceptual similarity shared by the two photos is that both are taken from a similar angle so that the viewer looks up at Jordan’s soaring figure silhouetted against a clear sky. This is a far less original element of Rentmeester’s photo, as photographers have long used similar camera angles to capture subjects silhouetted against the sky. But even here, the two photos differ as to expressive details in material respects.

In the court’s view, differences in selection and arrangement of elements, as reflected in the photos’ objective details, preclude as a matter of law a finding of infringement. Nike’s photographer made choices regarding selection and arrangement that produced an image unmistakably different from Rentmeester’s photo in material details – disparities that no ordinary observer of the two works would be disposed to overlook. If the Nike photo cannot as a matter of law be found substantially similar to Rentmeester’s photo, the same conclusion follows ineluctably with respect to the Jumpman logo.