Disney owns the copyrights to several well-known movies, including Beauty and the Beast, Frozen, Star Wars: Episode VII -The Force Awakens, Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, and Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2. Disney distributes its films in multiple formats through a variety of channels, including DVD and Blu-ray disc sales, on-demand streaming services such as iTunes and Google Play, and subscription streaming services such as Netflix and Hulu.

Among Disney’s offerings are “Combo Packs.” Combo Pack boxes feature large-type text reading, “Blu-Ray + DVD + Digital HD,” and include a Blu-ray disc, a digital versatile disc (“DVD”), and a piece of paper containing an alphanumeric code. The alphanumeric code can be inputted or redeemed at RedeemDigitalMovies.com or DisneyMoviesAnywhere.com to allow a user to “instantly stream and download with digital HD.” The exteriors of the Combo Pack boxes state, in somewhat smaller print near the bottom third of the box, that “Codes are not for sale or transfer.” Very fine print at the bottom of the boxes indicates, with respect to “Digital HD,” that “Terms and Conditions apply.”

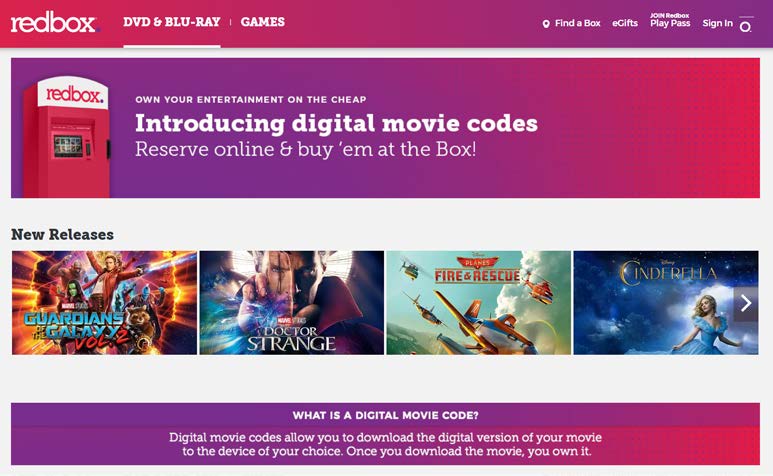

Defendant Redbox rents and sells movies to consumers via tens of thousands of automated kiosks that dispense DVD and Blu-ray discs. Redbox also offers a “Redbox on Demand” service that allows consumers to stream or download movies owned by studios other than Disney. More recently, Redbox has begun to offer digital downloads of Disney movies in the form of download codes.

Because Redbox does not have a vendor agreement with Disney, Redbox acquires Disney films by purchasing copies at retail outlets such as electronics stores, grocery stores, and the like. Redbox purchases standalone Blu-rays and DVDs as well as Disney’s Combo Packs. Redbox obtains digital download codes for Disney movies by purchasing Combo Packs and removing the piece of paper bearing the download code from Disney’s packaging. Redbox then places the piece of paper bearing the code into its own Redbox packaging and offers the code for sale at a Redbox kiosk.

Disney’s Complaint alleges inter alia that Redbox’s resale of Combo Pack digital download codes constitutes contributory copyright infringement, insofar as it encourages end users to make unauthorized reproductions of Disney’s copyrighted works. Disney moved for a preliminary injunction enjoining Redbox from, among other things, selling or transferring Disney digital download codes.

A copyright owner has the exclusive right to reproduce the copyrighted work. A defendant is contributorily liable for copyright infringement if he has “intentionally induced or encouraged direct infringement.” A copyright licensee infringes upon a copyright if he exceeds the scope of his license. By buying a standalone Disney code from Redbox and then redeeming that code on the licensed download service portals, end users necessarily violate the terms of the licenses and, Disney contends, therefore infringe upon Disney’s copyrights.

Redbox argues that Disney cannot demonstrate a likelihood of success on the merits of its contributory copyright claim because Disney has engaged in copyright misuse. Disney responds that it is not guilty of copyright misuse because it is not “trying to extend its copyright over the underlying movies to other, non-copyrighted products.” Copyright misuse extends to any situation implicating “the public policy embodied in the grant of a copyright.” The pertinent inquiry, then, is not whether the digital download services’ restrictive license terms give Disney power over some entirely unrelated product, but whether those terms improperly grant Disney power beyond the scope of its copyright.

The Copyright Act gives copyright owners the exclusive right to distribute copies of the copyrighted work. That right is exhausted, however, once the owner places a copy of a copyrighted item into the stream of commerce by selling it. In other words, once a copyright owner transfers title to a particular copy of a work, the transferor is powerless to stop the transferee from redistributing that copy as he chooses.

There can be no dispute that Disney’s copyrights do not give it the power to prevent consumers from selling or otherwise transferring the Blu-ray discs and DVDs contained within Combo Packs. Disney does not contend otherwise. Nevertheless, the terms of both digital download services’ license agreements purport to give Disney a power specifically denied to copyright holders by § 109(a). RedeemDigitalMovies requires redeemers to represent that they are currently “the owner of the physical product that accompanied the digital code at the time of purchase,” while the Movies Anywhere terms of use only allow registered members to “enter authorized… Digital Copy codes from a Digital Copy enabled… physical product that is owned by that member.”

Thus, Combo Pack purchasers cannot access digital movie content, for which they have already paid, without exceeding the scope of the license agreement unless they forego their statutorily-guaranteed right to distribute their physical copies of that same movie as they see fit. This improper leveraging of Disney’s copyright in the digital content to restrict secondary transfers of physical copies directly implicates and conflicts with public policy enshrined in the Copyright Act, and constitutes copyright misuse. Accordingly, Disney has not demonstrated a likelihood of success on the merits of its contributory copyright infringement claim.

Much of the parties’ briefing and argument focuses on Redbox’s contention that Disney’s attempts to prohibit transfer of digital download codes are barred by the first sale doctrine. Not all transfers of a copy of a copyrighted work constitute a transfer of title sufficient to trigger exhaustion of the copyright holder’s distribution rights. Under certain conditions, a transferee may be a licensee rather than an owner, and will not enjoy the protections of the first sale doctrine.

Redbox spends much of its opposition arguing that Disney’s transfer of a digital code in a Combo Pack does not bear the indicia of a license, and therefore should be considered a transfer of title to a particular copy. This argument misses the thrust of Disney’s position regarding the first sale doctrine. Disney does not argue that it transferred a restrictive license rather than title to a digital copy, but rather that the first sale doctrine does not apply here for the fundamental reason that the digital download codes are not “copies” in the first instance, let alone “particular copies.”

For copyright purposes, “‘copies’ are material objects, other than phonorecords, in which a work is fixed by any method now known or later developed, and from which the work can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device.” By Disney’s reading, no “copy” exists until a copyrighted work is fixed onto a downloader’s hard drive, and Redbox’s purchase of a download code therefore cannot possibly involve a “particular copy” to which a first sale defense could apply. Thus, Disney contends, this case is solely about the exclusive right to reproduce a copyrighted work, and has nothing to do with the right of distribution or, by extension, the first sale doctrine’s limitation on that exclusive right.

Redbox urged the court to conclude that Disney’s sale of a download code is indistinguishable from the sale of a tangible, physical, particular copy of a copyrighted work that has simply not yet been delivered. Even assuming that the transfer is a sale and not a license, and putting aside what Disney’s representations on the box may suggest about whether or not a “copy” is being transferred, the court could not agree that a “particular material object” can be said to exist, let alone be transferred, prior to the time that a download code is redeemed and the copyrighted work is fixed onto the downloader’s physical hard drive. Instead, Disney appears to have sold something akin to an option to create a physical copy at some point in the future. Because no particular, fixed copy of a copyrighted work yet existed at the time Redbox purchased, or sold, a digital download code, the first sale doctrine is inapplicable to this case.

Disney has failed to demonstrate a likelihood of success on the merits of its claims. The court need not, therefore, address the remaining preliminary injunction factors. Plaintiffs’ Motion for Preliminary Injunction was denied. The Disney has amended licensing terms on authorised digital services and filed new motion for injunction.